[Published n response to an English blog about Scientology.]

[Published n response to an English blog about Scientology.]

First. let me introduce myself. I’m Karin Spaink, a Dutch author and columnist, and I‘ve been sued by Scientology for no less than ten years on charges of copyright infringement, after I published excerpts of the OT-levels on my website. The courts kept ruling that I had legal grounds to quote; Scientology kept appealing each verdict. When the Dutch Supreme Court was about to rule in my favour, Scientology suddenly dropped the case. Ever since, it’s legal in the Netherlands to quote from Scientology’s purported ‘unpublished’ higher-level material, as long as the public interest is at stake.

My ten years of legal battles with Scientology have turned me into a bit of an expert of the cult. I’ve read a lot, studying both Scientology’s ‘official’ history, and stories from defectors and escapees. I’ve spoken with high-ranking church officials – such as Warren McShane, who at the time was heading RTC, one of the highest bodies within the organisation, and who is sometimes referred to as “David Miscavige’s top enforcer and crime boss” and with high-ranking church exits, from Jon Atack and Otto Roos (who used to be LRH’s private auditor), to Jenna Miscavige Hill.

In July 2007, a friend mailed me that an investigate news magazine article about a particularly violent group within the Dutch criminal scene, mentioned that murder-for-hire suspects Jesse Remmers and Peter la Serpe – both apparently involved in a number of highly publicized murders – were Scientology members. I made a blog post about it, quoting the article. Neither the Scientology reference in the original article, nor my blog post (a summary of which I also posted on the newsgroup alt.religion.scientology] received any attention from the press or from cult critics. I was OK with that – after all, there was only the *suggestion* that Jesse Remmers and/or Peter la Serpe possibly were, or had been, members of the cult.

The trial against the criminal group in question started in 2010. The court case – which dealt with at least seven murders, and was known by the moniker ‘De Passage moorden’ – took place in a highly secured bunker. There were unprecedented judicial efforts involved to bring the case to trial: the DoJ had invested a huge amount of time, and had accepted – a novelty, under Dutch law – a main suspect, Peter la Serpe, to act as its crown witness. La Serpe was going to testify against his former buddies; amongst them, Jesse Remmers. No mention was made of either Remmers or La Serpe’s possible ties with Scientology.

In October 2010, I was contacted by Remmers’ lawyer. She was eager to figure out whether Remmers had indeed been a member of the cult, and likewise, whether La Serpe had been. At her request, I witnessed the trial for three days, sitting in while Remmers and La Serpe were being interrogated, and even, at times, vehemently argued with one another.

Afterwards, I wrote a twelve-page report – extensive footnotes and all – for Remmers’ lawyer. I concluded that it was obvious that Remmers was a long-time member of Scientology, and that La Serpe had been a member for at least a good few years (but had meanwhile probably dropped out).

My arguments were threefold.

One: public sources. Records of the Dutch Chamber of Commerce, who also lists the membership of foundations, undisputedly state that Jesse Remmers had been on the board of the Dutch branch of Criminon, a Scientology front group. Also, in published interviews that Remmers and La Serpe have conducted with Dutch newspapers and magazines, both refer regularly to Scientology – something that non-members don’t tend to do.

Two: my own intimate knowledge of Scientology. An outsider might believe that a non-Scientology member could head one of the cult’s front groups, or that a front group might have rather ‘loose’ ties to the cult. Critics know that all Scientology front groups are strictly governed by the church, and that one needs to be a member in good standing within the church to become a board member of any of those. Together with Narconon and the CCRH (Citizens Commission on Human Rights), Criminon is one of Scientology’s best-known front groups. From August 2004 till December 2005, Jesse Remmers was the official “presiding director” of Criminon NL.

Three: language. Scientology uses an inordinate amount of highly specific jargon, and excels in phrases that are devoid of any meaning to non-members. When La Serpe talks about “clearing of overts” in an interview with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (September 23, 2007), it definitely rats him out as a Scientologist. In his interrogations during the trial, Remmers kept talking about ‘the tech’ and his ‘code of ethics’; he insisted that he had studied ‘the science’ and often spoke about ‘auditing’; all of which is Scientology shorthand. He even refers to Rule 22 of the Auditors Code, which prohibited from publicly acknowledging that La Serpe had confessed to him, in a private auditing session, that La Serpe had killed a prostitute.

Does La Serpe’s and Remmers’ established membership of Scientology have any bearings on their case? Would that knowledge have influenced the trial, and possibly have changed it, or would it have mitigated their sentences? Or, perhaps, could the membership of two self-proclaimed killers-for-rent, shed new light on the inner workings of the church, and prove that its inner teachings are inherently evil?

Some people have suggested that Scientology’s lesser-known ‘R2-45 policy’ refers to the option to “eliminate church enemies with the use of a Colt semi-automatic pistol (with .45 calibre ammunition”, and cite Remmers and La Serpe as possible adherents to this rather extreme policy.

Sorry – that won’t wash. La Serpe and Remmers admittedly killed quite a number of people, but not because they were Scientology critics. They killed them because they were hired to do so, or when they felt personally threatened, or when they panicked and didn’t know what else to do.

I dislike Scientology with a vengeance, but please don’t wash away these murders by pointing at your favourite target of criticism and shifting the blame on the cult. Scientology didn’t hire these guys to kill, Scientology didn’t order these murders, and nothing in Scientology’s (admittedly often villainous) policies would ever accommodate for the acceptance of, far less for the motivation for, such killings.

But their membership of the cult does indeed matter – in another way. It explains why Remmers, who had audited La Serpe a number of times, and thus got to hear about one of his earlier kills (the prostitute), never said a word about that to the authorities, not even while that same story – according to Remmers – showed that, years later, it wasn’t him who started shooting in a hangar, but La Serpe.

The judges wondered why Remmers brought up that story only now, while they were in court. Remmers’ answer was accurate, but unintelligible to anybody who is not versed in Scientology-speak. To summarize: “I had audited him. We had cleared his overt [which, earlier, had ‘caused’ La Serpe to kill the prostitute]. Years later, we were in a hangar, in a threatening situation. Suddenly, La Serpe reverted – he acted on his old overt, and started shooting. I couldn’t tell you [the court] about that shooting, because as his auditor, I understood why he did it, but I couldn’t talk about it with outsiders without breaking my ethics code as an auditor. Anything I would have said about La Serpe’s erratic behaviour in the hangar, would have brought up the prostitute, and what I learned by auditing La Serpe. So I kept mum.”

The court discarded Jesse Remmers’ explanation. I truly believe that, if they had known more about Scientology and its rules and methods, they would have taken Remmers’ testimony in a different vein. Which might have resulted in a lesser sentence for Remmers: on January 29, 2013, Remmers got convicted to life, mostly for the shoot-out in the hangar, which Remmers claims that not he, but La Serpe initiated.

Mostly, it’s rather interesting – hey, how’s that for an understatement? – to see how a cult that says that it is bent on eradicating crime and other ‘unsocial’ behaviour, has had its we-oppose-crime-so-aren’t-we-wonderful front group spearheaded by somebody who was by then already a known suspect for multiple murders.

You can’t blame Scientology for what Jesse Remmers and Peter la Serpe did, nor can their membership of the cult ‘explain away’ the murderous behaviour of these two. But you can wonder why a self-proclaimed, purportedly world-sanitizing religion would think that it’s OK to have convicted felons and known murder suspects act as its semi-public face.

Basically, that might go to prove that Scientology is currently so low on personnel, that they will accept anybody who shows up on their premises as an exemplary member who can tout their ideology. They are even happy with suspected killers.

[My report for Jesse Remmers’ lawyer is available on request. Send a mail to Karin Spaink, and I’ll send you a copy. Mind you, it’s in Dutch, and I have no intention to translate it…]

‘The Luscious’ was my nickname for her: Chris was voluptuous and generous. For more than thirty years, we were best friends.

‘The Luscious’ was my nickname for her: Chris was voluptuous and generous. For more than thirty years, we were best friends.

Boudewijn van Ingen (also known as Bogie) died last Tuesday, September 4. He was 49.

Boudewijn van Ingen (also known as Bogie) died last Tuesday, September 4. He was 49.

Today, I had the honour of delivering the keynote lecture at

Today, I had the honour of delivering the keynote lecture at

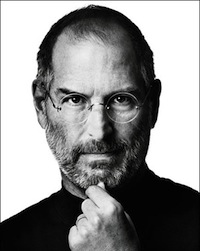

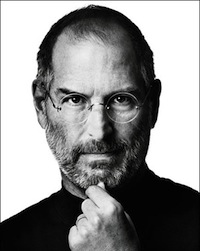

Something bugs me about the public comments after Steve Jobs’ death. Yes, he had pancreatic cancer; yes, it was discovered at such an early stage that an immediate operation might have saved his life. Yes, Jobs initially refused the procedure: he abhorred the notion that somebody would open up his body and fiddle with his insides. Instead, he opted for a strictly vegan diet.

Something bugs me about the public comments after Steve Jobs’ death. Yes, he had pancreatic cancer; yes, it was discovered at such an early stage that an immediate operation might have saved his life. Yes, Jobs initially refused the procedure: he abhorred the notion that somebody would open up his body and fiddle with his insides. Instead, he opted for a strictly vegan diet.

[Translation of

[Translation of  For years, it was unclear how the networking site Facebook makes profit. The amount of daily traffic a site generates weighs heavily in deciding the monetary worth of a web site, but invariably, there comes a time when actual revenue starts counting and mere ‘hits’ are no longer sufficient. How does Facebook earn its money?

For years, it was unclear how the networking site Facebook makes profit. The amount of daily traffic a site generates weighs heavily in deciding the monetary worth of a web site, but invariably, there comes a time when actual revenue starts counting and mere ‘hits’ are no longer sufficient. How does Facebook earn its money? (Article in the catalog of the ‘Embody’ exhibition by Chaja Hertog and Nir Nadler, Israel, 2008. I met Nir while I was a mentor at

(Article in the catalog of the ‘Embody’ exhibition by Chaja Hertog and Nir Nadler, Israel, 2008. I met Nir while I was a mentor at  [Originally published in Het Parool; translation by Anonymous, at

[Originally published in Het Parool; translation by Anonymous, at

Critique of Andrew Keen’s The cult of the amateur

Critique of Andrew Keen’s The cult of the amateur