Questioning McShane

Stockholm, Friday, May 29 1998

[Previous installment: You know that you’re being sued by Scientology when] 9:35. Court resumes. Magnusson speaks.

That is, he utters a word, waits five seconds, then utters another, waits, scratches his head, says a word, waits, leafs through his papers. The judge looks puzzled. Now what is this man doing, he wonders. “Are you done?” he asks. “… erm, … No…” Magnusson replies, and moves to the next word. Zenon and I exchange glances. Yesterday, Zenon asked Magnusson what the fuck had been amiss with him earlier that day, when he literally spelled his words. Gotten out from the wrong side of the bed? Ill? Fight with the missus? “No, not at all,” Magnusson had answered, “I was just trying to emphasise my words.” Instead of attracting he’s losing everybody’s attention. “OT2… OT3… NOTS… materialet… erm… hemlig… ehh… RTC… materialet…”

His aide gets up and hands a set of papers to the three judges and the clerk, then sits down. “Erm, shouldn’t you give one to Panoussis as well?” the judge reminds the aide. The aide smiles bashfully, gets up again and does so. It turns out to be a fifty-page brief containing a phrasal of the grounds, ‘grounds’ being the legal reasons you put forwards as to why your opponent is in the wrong. The judges sigh. “Now which parts did you revise?” the chairman asks Magnusson. “You don’t expect us to read all this again, do you?” Yes, I think he does. Worse, Magnusson expects them to carefully compare these grounds to the ones he previously handed in. Perhaps the court should hire a notary public to compare the two sets; now, that would be a novel idea!

There is a discussion about the damages RTC claims it has suffered because of the availability of “the material”. Zenon insists that RTC should specify its claim (it has been proposed as a lump sum). Zenon again mentions ‘Excalibur Revisited’, written by Geoffrey Filbert, a book that deals with OT3 stuff too and which was registered with the Copyright Office before Hubbard’s OT3 was. McShane immediately confers with Magnusson.

From my comments & summary re: OT3: “Excalibur Revisted was published in electronic form, and Mr Filbert has given it to the public domain in the fall of 1994. It is, amongst others, available via America Online and has been since December 1994. The material is in fact copyright by Filbert; he received his copyright registration on April 25, 1982. Scientology received their first copyright filings for their OT 3 material in 1986… So I guess Filbert predates them.” Filbert describes something very similar to OT3 in pages 266 – 268 of his book.

10:20. McShane takes the witness stand again. I didn’t understand most of Magnusson’s questions so I’ll leave these open; McShane’s answers are more or less verbose. (There will be a tape via the court later, so don’t take my word for it.)

Q ..

The majority of L Ron Hubbard’s works are freely available, perhaps 95% is there for all to read. There is a small percentage that is confidential, that he designated as such, and we believe that this material should remain confidential and unpublished and is only to be seen by and sold to individuals who have reached a certain qualified spiritual level.

Q ..

No you do not.

Q ..

Before a member can have access to, for instance, OT2 he has to go through all prior steps and levels, which can take a considerate amount of time, and only then he becomes eligible to apply for permission to have access to OT2.

Q ..

Once he has qualified spiritually, having met the prerequisite requirements, he then has to apply to RTC to get access. RTC then makes sure that he has indeed met the correct spiritual requirements and that he has the correct ethical — now that is a church term, it means ‘moral’ — requirements to study OT2.

Q ..

Yes we do.

Q ..

No there is more.

Q ..

Once RTC has authorised a person to be allowed access to the level, he then has to sign a confidentiality agreement, and if it has been verified that all requirements are met, he then is invited to study the material. He will take that invitation. The confidentiality agreement is an agreement that the members signs and whereby he agrees that he will never copy the material, never take notes of the material, that he will never disclose the content of the material, that he will maintain the security of the material. That he maintain the security of the material while he is on that particular service. ‘Service’ is a word we use for a special course or counselling you will be receiving.

Q [hands McShane a binder; the attachment under scrutiny is a confidentiality contract] … Can you briefly …

The example here in the book is a typical confidentiality agreement that the member will sign before he is allowed unto the level, and it specifies exactly what is required from this member. For example, the second page of the agreement, where you have no 3, it says that the parishioner specifically agrees that the Advanced Technology, including those portions which have been trusted to him,

Q ..

FSO stands for Flag Service Organisations, one of our largest service centers, and it is located in Clearwater, California.

Q ..

Under 4a it says: “the parishioner shall not disclose verbally [stuff which I missed] …”. That kind of encompasses the meaning of this document in general terms.

Q ..

Next he would take this signed agreement and go to the RTC representative in the Advanced Church, and he would receive an invitation to study this specific level he is applying to.

Q ..

Once he has done those two steps, he has to read the security regulations which gives him more information as to what is required of him while he is on the course. This reference gives him specifics as to how to access the security rooms where this material is kept and where he will do his course. For instance, he is not permitted to let anybody into the room that does not have his own security card, which is a card you need to gain access to these rooms.

This binder contains photographs of the procedures that are followed by all parishioners who are selected to do an OT course. Although the photos are depicting the procedure [..], this is the procedure which is followed by all members who are allowed access. I will go through them as quickly as I can. [blabla. McShane explains the security procedures in great detail and keeps at it for half an hour. Cards, guards, chains and locks.]

The courses contain more than just the confidentiality material, there are also confidential tapes that contain Mr Hubbard’s lectures. These tapes never leave the room. .As for the NOTS, members are not allowed on that course, it is allowed only to the ministers of the Advanced Organisations.

Break.

11:30. McShane continues.

There are only seven churches in the world that are authorised by RTC to deliver this material.

Q ..

No, there’s none in Sweden.

Q ..

The general purpose of these magazines is to inform the members what is happening in the church – events, marriages, conferences — and also they promote the services that that churches offers. [He is obviously trying to repair some of the damage Zenon has done when he quoted form CoS promo material.]

Q ..

No, it talks about all the services which contain a lot of the non-confidential services and some of the confidential services that are delivered by these organisations.

Q ..

Yes, these are two organisations which are licensed by RTC.

Q ..

That means that — ‘clear’ is a specific level which is one of the services these organisations deliver. Panoussis had it wrong, he believed the OT levels come first, then clear, which is not true. [A couple of the critics exchange surprised glances. Zenon never said so. Zenon knows that ‘clear’ comes first.] The level of ‘clear’ — although there is a course involved that is confidential, the clearing course — people can reach the state of ‘clear’ without doing that course. It is a very significant level in the church. After a person has achieved the state of ‘clear’ he would then be eligible to continue on with the OT levels. The number I believe that is listed in there for OT levels is not how many OT’s have been produced but how many levels those people did.

Q ..

You have OT1 to OT8, those are what we call the OT levels. And once a member completes for instance OT1, he then becomes eligible to become OT2, and so on. So, for instance, if there was just one person in that part church who did seven levels, the magazine would list them as seven completions.

Q .. [I think: whether it is possible to do all levels in the time covered between the release of two issues of a magazine]

It’s possible.

Q ..

For instance, here, on page x, it says ‘over 2000 level completions’, a number from which you can’t tell how many individual people have done these levels.

Q ..

On the first page it says 2500 clears; ‘clear’ is not an OT level And then it says over 1000 OT’s per year, which means that there could be a 1000 different persons who did a level, for instance OT1.

Q .. [how many people did them]

I can give you a fairly accurate estimate. Since 1968, when OT2 and 3 were delivered for the first time, there are in between 20,000 and 25,000 people who have gone through the specific requirements and past all the other requirements. That’s a pretty good estimate. In comparison to the membership of Scientology all over the world, that is pretty small.

Q ..

The NOTS course itself is for specially trained ministers of the church and there’s a — my best count is 325 ministers.

Q ..

The course itself, for instance the OT2 course, contains many different texts, tapes and videos by Mr Hubbard, and together that makes up the OT2 course. So it’s more than just the OT2 materials that go into the course.

Q ..

Unfortunately, in 1983 several ex-members of the church, three, impersonated high executives of the church and went in to the Advanced Organisation in Denmark and stole material that was specifically the NOTS material; and another theft occurred in the Advanced Organisation in the UK, also in 1983, where an employee stole a copy of OT2 and OT3. One of the people who stole the material in Denmark was arrested and imprisoned for the theft and the authorities recovered the original material, including OT2 and OT3, but unfortunately, the pirated copies were not all recovered. These individuals intended to start and in fact did set up a competing organisation in the UK where they provided services utilising these materials for their own personal profit.

Q ..

No its not standard; it usually take a couple of years before one becomes eligible.

McShane leaves the witness stand. Another discussion about schedule & time ensues. Magnusson talks again about Filbert. There’s some arguing about publication dates of his work and Hubbard’s OT3.

12:15. Lunch. Zenon and I go through our notes. Zenon has decided that I will be his aide again and will sit next to him in court, with my computer, ready to flood him with information if necessary.

During lunch, journalists show up again. The press has been covering this trial rather well. We are presented with copies of the Swedish edition of “Freedom” that deals with Zenon, me, and Newkid.

13:15. I sit next to Zenon, laptop ready, just like he has his. This side of the court represents the net section, that much is for sure.

Zenon asks the court whether Magnusson has finally decided if he can have a copy of Attachment 126 section 143, which contains comments on and a summary of OT3. Zenon has crossed out all of Hubbard’s quotes and accepted that these will be left out of the RTC-approved copy he is asking for, and yet Magnusson and RTC refuse to decide whether to provide Zenon with one. They consider 126/143 to be sealed and copyrighted. Magnusson is not yet sure. He stalls again. Erm, well, yes, now, erm, [scratches head] “Perhaps on Tuesday?” On Tuesday it shall be, the court decides, and not at the end of the afternoon, the chairman adds emphatically.

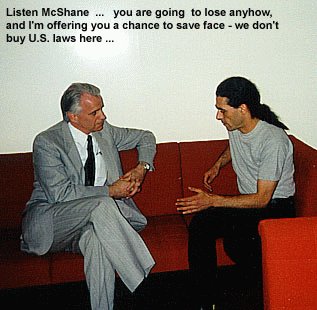

Our turn to interrogate McShane. [My notes here are more concise; I worked, meanwhile.]

Zenon asks about Filbert and ‘Excalibur Revisited’.

McShane: “Yes, I have read Mr. Filbert’s book. It was never published. What he took from Mr. Hubbard is small and was taken from Mr. Hubbard’s work. If you put those bits together, it’s only a paragraph or two — if you can put them together at all — out of as many as two hundred pages.”

Zenon wants to know about Attachment 126/document 134. Why does RTC not want to give him a copy?

McShane: “It’s just too many quotes.”

Zenon asks about the requirements to become OT.

McShane: “As I explained previously, they have to have acquired all necessary spiritual levels.”

Zenon: “Can you do those on your own?”

McShane: “No.”

Zenon refines the question, wishing to know whether in that case it is CoS’s help which is necessary to study the OT-levels.

McShane: “I don’t know what you would do, you’ve started your own church. All I know is what the CoS would do.”

Zenon refines again. Magnusson objects. The court allow Zenon his question. “Can you study to become OT without the CoS’s help?”

McShane: “No one could obtain the same level without the church, but people have tried, for instance with material obtained from the net.”

Zenon wants a definite answer: is the help of the church a prerequisite to become OT? Magnusson interrupts and objects again. The court allows Zenon to continue. He states his question again: Does CoS believe that only they, and no one else, can train people adequately to become OT? Yes, or no?

McShane: “Yes.”

Zenon: “In preparations to become OT, can you just do parts of an OT level? For instance, will studying parts of OT3 do?”

McShane: “No.”

Zenon: “The same goes for OT2?”

McShane: “Yes.”

Zenon: “What is the exact number of pages?”

McShane: “Erm, I’m not sure… I think the whole course is 200 pages.”

Zenon: “Maybe 300?”

McShane: “Possibly. I do not have them on me.”

Zenon: “OT3?”

McShane: “I think 200 pages.”

Zenon: “That is correct.”

Next subject: security. Since when was this massive security implemented? Magnusson objects and wants to know what the relevance of this question is. Zenon retorts: “The relevance of this question is that you have just interrogated your client about these security measures for one hour.” The audience laughs. “And can I please have my next interruption now?” Zenon adds. He’s fed up with Magnusson’s continuous bickering.

McShane: “There has always been some, depending upon the available technical possibilities.”

Zenon: “And since when do you apply this confidentiality agreement?”

McShane: “Since 1968, when OT2 and OT3 were released.”

Zenon wants to know whether people had ever been allowed to take them home.

McShane: “People have never been allowed to bring them outside the church.”

Zenon: “And the materials have never circulated outside the church since 1968?”

McShane: “No.”

Zenon: “Are you familiar with the name Sherm Frederick?”

McShane: “Who? No.”

Zenon informs him that Sherm Frederick was the editor to a Las Vegas newspaper that wanted to print part of the OT materials. When CoS sent somebody [RV Young] over to investigate, in August 1980, it turned out Frederick had full copies of OT 1-5.

McShane claims he does not know.

Zenon wants to know what an ‘SP’ is.

McShane: “An SP, or a Suppressive Person, is somebody who engages in anti-social and destructive acts, acts that go against humanity. For instance, Hitler.”

Zenon: “Why was Bill Robertson declared to be an SP on 26 May 1982?”

Magnusson interrupts. The court allows Zenon his question. Zenon: “So, did Bill Robertson get declared SP for starting Galactic Patrol and using OT levels?”

McShane: “The material was his own creation.”

Zenon: “Have you ever heard of the magazine ‘Heretic’?”

McShane: “Heretic? No.”

Zenon: “I’m happy to inform you that it discusses the OT levels and carries quotes of it.”

McShane: “I am not aware of that.”

Zenon: “Were there ever copies of OT documents in the Clearwater Court, open to the public?”

McShane: “Not to my knowledge.” [Comment: as a matter of fact, there were: in 1985, documents containing OT levels were in the Clearwater Court. CoS went through the same routine as they are now performing in Stockholm’s Tingsrätt: asking for it day in, day out, and preventing others from retrieving it. Yet the LA Times got themselves a copy.]

Zenon: “Are you familiar with ‘Revolt in the stars’?”

McShane: “Yes, I am. I have read it.”

Zenon: “Are there parts of OT3 in it?”

McShane: “No.”

Zenon: “Is there anything from OT3 in it?”

McShane: “I do not know what you mean by ‘anything’.”

Zenon: “Something which you would consider to be a quote.”

McShane: “No. There are no quotes in ‘Revolt in the Stars’ which were taken from OT3. ‘Revolt in the stars’ is a screenplay, it is fiction, and it deals with characters, some of whom — who live some of the things that are described in OT3. It is a fictional work.”

Zenon: “Does the US government or any of its authorities have copies of OT levels?”

McShane: “No, not that I am aware of.”

[Comment: RVY has testified that, when CoS requested files from the US government and the FBI, under the Freedom Of Information Act, it turned out that they had copies of the advanced technology-material. According to RV Young, this was in 1974, ’75.]

Zenon: “Are you familiar with the following quote from a recent court case you were involved in?” Zenon starts reading him the quote and yes, Magnusson interrupts. After some hassle Zenon is allowed to continue. Seeing that the quote is in English, he decides to bring my computer to McShane: that way he can read it directly and the court’s interpreter can interpret it for the court: “Despite RTC and the Church’s elaborate and ardent measures to maintain the secrecy of the Works, they have come into the public domain by numerous means. RTC’s assertion that the only way in which the materials have escaped its control was through two thefts in Denmark and England was not supported by the evidence. A former senior Scientology official testified to ongoing difficulties the Church incurred in keeping the Works secret, including members losing materials in their possession.” (Judge Kane, RTC v FactNet, Civil Action No. 95-B-2143, September 15, 1995 at Denver, Colorado.)

McShane: “I do not remember the quote.”

Zenon: “It was an important case.” He mentions judge and case.

McShane: “… This was a ruling in a preliminary hearing. [Or did he say: ‘summary hearing’? I’m not quite sure.] I do not recall it.”

Next subject. Or rather, a previous one.

Zenon: “In your opinion, can people outside the church who have access to the material, become OT?”

McShane: “The only Scientology churches are those that are authorised by RTC.”

Zenon: “That is not what I asked. Can only CoS properly educate people to become OT?”

McShane: “We have no view on other groups outside the church. Except when they use infringing material. If they use other material — that they believe is Scientology material — we don’t care.”

Zenon: “I am not asking about infringements. The question is, what is the stand of RTC towards congregations outside the CoS that use RTC material that is not infringing, such as for instance published RTC material that has been legally bought?”

McShane: “If there is a group that uses Scientology material that was authorised I have no view. If they are using infringing material we try to make them stop. It’s illegal.”

Zenon: “Are there people that RTC is currently suing over, not over copyright but over trade secrets? How many of such actions has Scientology initiated in the past four years?”

McShane: “Seven cases — it’s more copyright, some of them involve specific trade secret claims as well — in the US, in Holland, and here.”

Zenon: “I meant trade secret.”

McShane: “Oh I thought you meant either way. I think three.”

Zenon: “When you confiscated my hard disk, you stated -” Magnusson interrupts. Zenon: “Again?” There is some debate between Magnusson, the court and Zenon.

Zenon: “When you confiscated my hard disk, you had some search terms. Among them, was there ‘Ward’ and ‘Vorlon’?”

McShane: “Possibly. I do not remember.”

Zenon: “Are those words in OT2 or OT3?”

McShane: “No, it’s people who posted the infringing material to the net. We were looking for the people who posted that.”

Zenon: .. [didn’t get that]

McShane: “I believe so. I figured that if she [= the bailiff] found those names, she’d find those infringing works.”

14:20. Break.

After the break, it’s the computer expert’s turn again. He is again asked about Zenon’s message of May 2, in which he announced he was going to post the NOTS. Magnusson wants to know whether headers can be manipulated (yes, they can) and what this experts thinks the chance is of this one being authentic. “Ninety-nine percent,” he answers. They go on about the message. When it’s Zenon’s turn, he tries to explain to court, via the expert, that anybody who has a direct connection to the net, can inject postings in a newsfeed. The expert admits that this is possible. But only big companies have direct connections to the net, he says, and it sounds as if only Volvo can have one. “Does your company have one?” Zenon wants to know. “Yes.” “And how many people work there?” “Forty. But we do webpages and code and stuff.” “Wouldn’t such companies be precisely the ones where the knowledge to inject such a posting can be found?” “Yes,” the expert agrees.

15:15. The expert is done.

Zenon asks for McShane’s tapes, including those of the closed hearing when Magnusson, McShane, Zenon and the court went through attachments 24, 37 and 126. Magnusson says he can reply on Wednesday. Zenon insists: he needs them in order to prepare for his final plea, which is to be on Wednesday, and apart from that nothing from “the material” was read aloud. Magnusson hesitates again. He would need to confer with his client in order to reach a decision so that — “For god’s sake,” Zenon exclaims, “the only secret words mentioned there were ‘BT’ and ‘cluster’. There. Now, can I please have a copy of the tape?”

The court adjourns. Next session: Wednesday, June 3.

[Unbiased columnism is a series of seven court reports on the proceedings of Scientology versus Zenon Panoussis. This series covers the May 22,1998 – June 3, 1998 sessions. Next: Final Pleas.]